Islam, in the form of the Ottoman Empire, laid siege on Christian Vienna for two months in 1683. This was experienced by all combatants as a do-or-die moment for faith. If the Ottomans won, Europe might become significantly more Muslim in the future. If the Holy League (Polish-Lithuanian, German, Hungarian, Austrian soldiers) won, Europe would remain Christian. When the Holy League proved victorious on September 12, 1683, the King of Poland, Jan III Sobieski said, "venimus, vidimus, Deus vincit." We came, we saw, God conquered.

Three hundred and twenty-eight years later the same battle line was drawn in the mind of a man named Anders Behring Breivik at government headquarters in Oslo, Norway, and on the small nearby island of Utoya. In targeting government offices and the next generation of Norway’s political left (mostly Christians) to drive home his hatred of Islam, Anders saw himself as again stopping the Islamization of Europe.

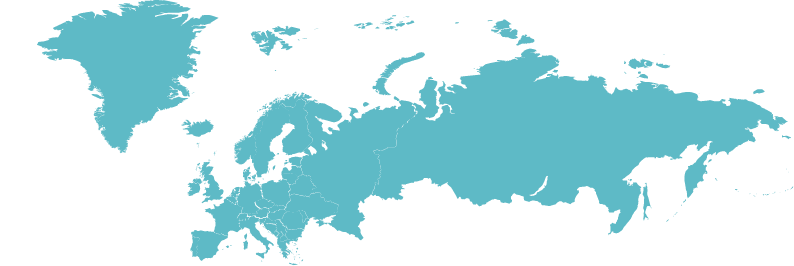

King Sobieski had approximately 80,000 behind him as he rode into battle. How many were behind Anders Breivik? Not just in Oslo but in the rest of Europe? How many people have been watching the rising tide of Muslim immigration and wondering, where will this lead? With normal birthrates down and immigrant birthrates soaring, how long before the tipping point? Then what will Europe look like?

Although few would endorse the violence espoused by Anders, the undercurrent of fear that nurtured his fanaticism is prevalent across the continent and beyond. A poll earlier this year in Germany showed 55 percent of Germans believing that Muslims were a burden on the economy, and another found that 40 percent view Muslims in Germany as a threat. Polls in France found similar numbers. Far-right parties are on the rise. So clearly Anders is not the only European asking these kinds of questions, and perhaps even harboring dark thoughts.

In the 17th century, the logical conclusion to these issues was holy war. A handful of extremists on both sides—Anders among them—would argue for that conclusion today. But for most of us, violence in the name of God, any God, is not an answer, it is a blasphemy. But if the point is not to take up arms in the cause of exclusive righteousness, then what can people do to cope with the very real changes happening in their communities?

Coping means to hold out for something holier than murdering in the Name of God. It means aiming for a broader embrace. Showing hospitality to strangers. Learning something new from foreigners. Making room for the new arrivals. Coping is more than sweeping legislation by politicians and well intentioned decrees by religious leaders. It requires local people to meet each other across the cultural and religious divides and to create a sense of community around the issues that heretofore separated neighbors.

Hard work! How does it get done? By one person stepping forward and finding others who are willing to engage and then getting started on some mutual project. Through United Religions Initiative I have seen it happen hundreds and hundreds of times in more than 75 countries. People have come together in a principled way to create cultures of peace, justice and healing.

Shooting it out is no more a credible option today than is staring it out in rage or passing by in indifference. The only option we have today, if we are to have strong and healthy communities, is to come together and build an extended family. The deep tears of Norway are a testimony to the futility and insanity of annihilating people in order to preserve religious purity. This is not the time to pour energies into "stopping the Islamization of Europe”; this is the time to create a Europe where the Christian God and the Muslim Allah conquer together.