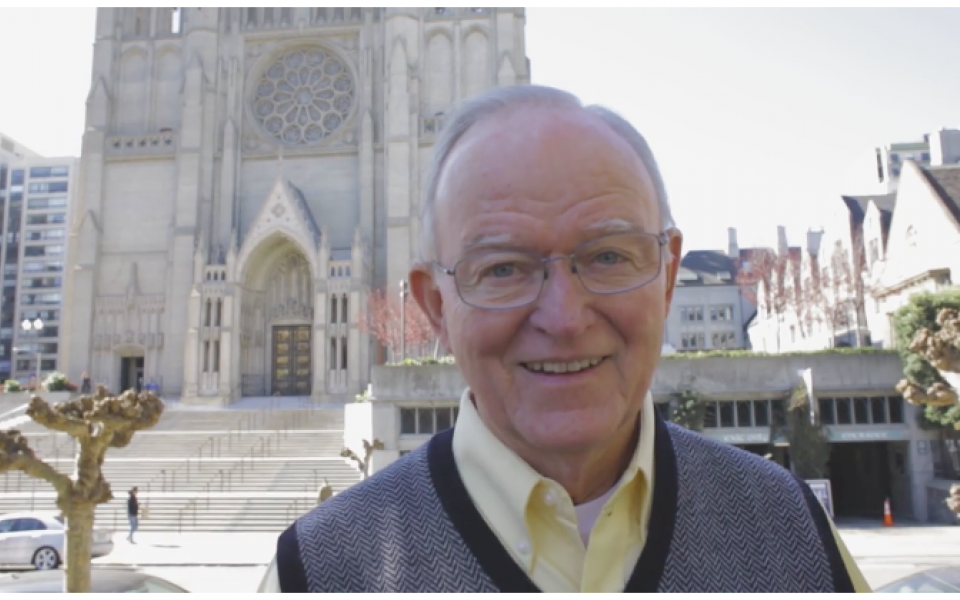

Bishop Swing at Grace Cathedral (Media: SF Chronicle)

March 3, 2018 Updated: March 22, 2018 7:15pm

Published in the San Francisco Chronicle

Bill Swing’s big idea ran into trouble almost immediately after he thought of it 23 years ago.

Yet Swing’s widely rebuffed notion — to create a United Nations equivalent for the world’s religions to work together in peace — is today a million-person global powerhouse that educates children, fends off terrorist recruitment and, improbably, turns religious opponents into allies in 104 countries. So far.

How Swing effected change for the good around the world is a story of ingenuity and, some might say, extraordinary vision nourished by compassion.

As a bishop and leader of California’s Episcopal Church in 1995, the Rt. Rev. William Swing believed he was in a good position to rally the world’s religious leaders behind his United Religions Initiative.

His track record of successful activism also encouraged optimism. He’d flown into the civil war in El Salvador and helped arrange the release of 23 imprisoned church workers. He’d visited San Francisco’s Castro district each week to hear the life stories of gay men being struck down by an unknown disease, and had held the Conference on Religion’s first AIDS response forum. He’d jump-started negotiations to build a new St. Luke’s Hospital in the city and had begun Grace Cathedral’s shelter program for 1,500 homeless people.

Then, after Swing hosted the United Nations’ 50th anniversary service at Grace Cathedral in 1995, he conceived of United Religions and set off on a five-month quest with his wife, Mary, to introduce the cooperative idea to religious leaders of the world: the pope, the dalai lama, Jerusalem’s chief rabbi, Egypt’s grand mufti and the archbishop of Canterbury among them.

He was stunned when they expressed no interest.

But Swing had another thought: “It dawned on me that the grassroots people of all faiths were the key,” he said.

If those at the top turned him down, he reasoned, why not try those at the bottom? So he and Mary took another trip. They hired a staff, hosted interfaith events around the world — welcoming tribal members and atheists into the mix — and went $800,000 into debt.

Now, Swing is one of six nominees for The Chronicle’s 2018 Visionary of the Year award, which provides a $25,000 grant toward the winner’s work.

Swing’s work, the United Religions Initiative, isn’t actually about religion.

“We assume that the world has enough religions,” Swing said. “But we assume that the world doesn’t have enough bridges between those religions to make the world better.”

The system works through “cooperation circles,” and there are hundreds of them. Swing said anyone can start a cooperation circle with at least seven people and three different religions or traditions. Self-funded and self-governed, circle members choose a purpose — the arts, education, the environment, human rights or any other — and adhere to the main organization’s principles, which are replete with such words as peace, justice, cooperation and respect.

Some cooperation circles are vast, with huge budgets. Some are tiny. They pay no money to the organization’s headquarters in the Presidio of San Francisco, which employs 37 people, and no money flows out to the circles, Swing said.

In all, the group calculates it has about 1 million participants. Its newest circle is Saudis for Peace, composed of Shiites, Sunnis and Christians in Saudi Arabia.

In Cameroon, a circle of Christians, Muslims and tribal members runs a computer lab so youth can see an alternative to becoming Boko Haram terrorists, according to the organization’s website. A Middle East circle unites Israelis, Jordanians and Palestinians in restoring the polluted Jordan River. And in Florida — one of 108 circles in the United States — Christian, Jewish, Muslim and Buddhist women have met for a decade, doing charitable work and opposing hate crimes.

“When you devalue human beings, you can lynch them, you can gas them, you can line them up and shoot them,” Swing said. “You can destroy their villages and towns. Imprison them and torture them — all in the name of God.”

Swing’s big idea was to offer something different.

He was nominated for the Visionary award by former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz and Charlotte Shultz, the chief of protocol for California and San Francisco. The bishop married the couple in 1997.

The United Religions Initiative “is one of the most constructive things going on anywhere in the world today,” George Shultz said.

He and Swing are in a cooperation circle called Voices for a World Free of Nuclear Weapons, whose eight members include Jews, Hindus and Christians.

“People don’t get together and talk about their religions. They talk about some problem they need to solve,” Shultz said. “That’s very important in a world where there’s a lot of tension around religions.”

Charlotte Shultz agreed. She called the organization — and its founder — extraordinary.