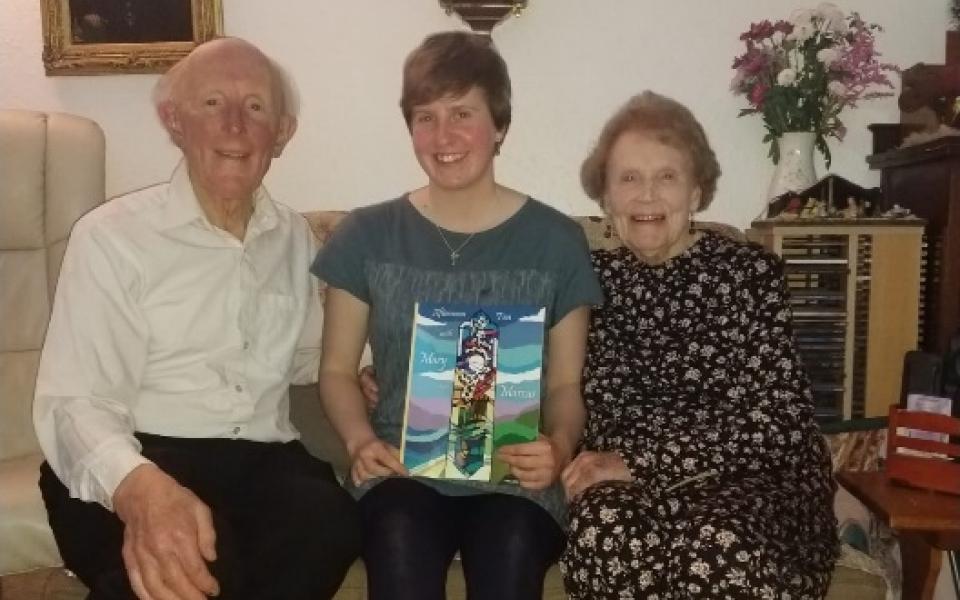

Helen Hobin, author of Afternoon Tea with Mary and Marcus, pictured with her grandparents Marcus and Mary Braybrooke.

Marcus and Mary Braybrooke are pioneers in the interfaith movement. Marcus and Mary were with URI in its earliest days and continue to support URI and interfaith efforts with enthusiasm and wisdom. Marcus’s book, Pilgrimage of Hope – One Hundred Years of Global Interfaith Dialogue and Widening, provides a thoughtful perspective of the roots of the interfaith movement. His words to a URI global assembly are worthy of posterity:

“When we participate in interfaith work, we must take off our shoes, because we are entering holy ground.”

A new book, Afternoon Tea with Mary and Marcus, written by their granddaughter, Helen Hobin, is warmheartedly reviewed below by Paul Chaffee, a founding Global Council member and Cooperation Circle (member group) leader in URI.

With deep gratitude,

Sally Mahé

Afternoon Tea with Mary and Marcus, by Helen Hobin

A review by Paul Chaffee

Reading a lengthy self-published family history (unless it’s your own) is probably low on your wish list. Afternoon Tea with Mary and Marcus (2019), however, jumped to the top of my ‘to read’ pile when it came in the mail. No one yet has written a biography of Marcus Braybrooke, born in 1938 in Dorking, 20 miles south of London. Along with pioneers such as Juliet Hollister, he opened the floodgates to intentional interfaith engagement in the world, starting in the 1960s. Marcus’ 40 plus books on faith and interfaith offer a wide-ranging library focused on interfaith-based relations historically, spiritually, and liturgically.

Afternoon Tea, on the other hand, takes us straight into the particulars of his life and relationships. It is a treasure.

That said, the book is much more than a bio of the Rev. Dr. Marcus Braybrooke. It was written by Helen Hobin, one of Mary and Marcus’ granddaughters, a camera technician for BBC’s wildlife productions. The story encompasses an extended family thriving in an environment without television, the internet, or social media, and how they have adapted to a transformed world. Hobin’s prose is lively and compelling. She depends on extended conversations and letters from dozens of family members and friends who have known and worked with the Braybrookes for decades. Childhood, school, romance, vocational history, community engagement, high times and low, international travel – the details are here.

As the title suggests, Mary Walker Braybrooke is fortunately given as much ink in this study as her spouse. Born in 1935 in Cambridge, as a teenager she was drawn to interfaith concerns through the interfaith services she attended at her Unitarian Universalist church. Her career as a social worker (and distinguished trainer of social workers), focused on the most difficult circumstances people suffer, including mental illness, addiction, kidney and liver diseases, terminal illness, and domestic and child abuse. Colleagues say she generated joy in building strong relationships with the distressed. A second, part-time vocation came in the 29 years she spent as a magistrate. In Bath at first and later in Oxford, she spent an afternoon each week devoted to addressing crime and neighborhood problems.

Over the decades, the most striking feature of Mary and Marcus’ life is the partnership infusing everything they do. She is the fun-loving, sometimes “naughty” extrovert, with progressive ideas. He is quieter and gentle, a pastor whose sermons are compelling and a teacher known for his sense of humor. Unexpectedly they really click, though he had to prove himself through a lengthy courtship. Together they pioneered a new kind of religious consciousness and leadership, more open and tolerant and shared.

Their ministry was hand-in-glove in their early years at various parishes. Mary participated in worship and organizing church activities, while Marcus engaged as much in the local community as the congregation. The churches they served, all within about a hundred miles of London, grew and thrived, leading to a number of seminary, ecumenical, and interfaith posts for Marcus. Again Mary and Marcus treated these assignments as a shared ministry. Eventually, when Mary retired from social work, she joined her husband in his numerous global jaunts, helping build a network of interfaith-inclined religious leaders around the world, most notably in Asia.

Marcus’ penchant for international travel began through two years of mandatory English ‘In Service’ work. He enlisted at 17 and served in Libya and Cypress. He managed to schedule in a week’s visit to Jerusalem, Galilee, and the Dead Sea.

Back in England, he spent four years at the University at Cambridge, joining the Liberal Club and the United Nations Association as well as the Pastorate, a group of students who gathered over tea on Sunday afternoons for religious dialogue. From his early teens, Marcus had known he wanted to become a clergyperson. At Cambridge, one particular sermon at Holy Trinity Church inspired a life-transforming grounding: “I realized that I no longer had to try to be a good Christian – all I needed to do was hold fast to the assurance that God loved me as I am.”

Following university, Marcus secured a World Council of Churches scholarship funding a year of study at the Madras Christian College in India. In Madras (today renamed Chennai), the young man found himself submerged for the first time in a non-Abrahamic culture and religion. He began developing interreligious friendships, a practice which continues to this day.

The list of friends includes religious makers and shakers such as the Dalai Lama, Maha Ghosananda, Daniel Gomez-Ibanez, Hans Küng, and William Swing. But there are many hundreds more. As a priest, primarily, rather than an academic, Braybrooke felt an ethical compulsion to be more than a scholar, to be an activist, engaged in the interfaith cause. Educated in Cambridge, retired in Oxford, with a long shelf of books, it’s easy to think of him as an academic. He’s taught in many a seminary and lectured at dozens of universities.

But his vocation has always been pastoral. He is a prototype of the thousands of local clergy in countries across the world this past half-century who have found interfaith relationships integral to their pastoral ministry, an enhancement, not a substitute for their own traditions. He was near the front of the line in this movement, and he and Mary have demonstrated an awe-inspiring tenacity in pursuing friendship with the stranger.

As a part of his priestly role, we watch Braybrooke’s early involvement and decades of work helping to sustain the World Congress of Faiths. We witness his work with a distinguished Jewish rabbi and Muslim sheik as they founded Three Faiths Forum (today the Faith and Belief Forum), the largest, most active interfaith organization in the UK. He and Mary were there when United Religions Initiative was barely more than a good idea. He wrote Pilgrimage of Hope – One Hundred Years of Global Interfaith Dialogue and Widening Vision (1992), a history of the interfaith movement from the first World Parliament of Religions in 1893 to the Parliament of the World’s Religions in 1993, both held in Chicago. Actually, Marcus and Mary attended several centennial interfaith Parliament celebrations in 1993, as detailed in Afternoon Tea with Mary and Marcus.

When the Archbishop of Canterbury conferred a Doctor of Divinity on Marcus in 2004, his commendation began: “A Hindu has said, ‘Marcus Braybrooke has probably contributed more than anyone else to the development of interreligious cooperation and understanding throughout the world.’” In short, the interfaith movement’s debt to this man is immeasurable. But the delight of Afternoon Tea is that it gives us the personal lives of the whole remarkable family.

Let me conclude with a passage from the last page of this biography, which is available on Amazon. It is a good example of what the good life can mean in a family, told with the polished ease of Helen Hobin’s prose.

Gathering at Springend Cottage, Devon, in November 2018 we celebrated Marcus’ 80th birthday … We were surrounded by loving family and friends. The house itself seemed full of light, amid the decorations and the marvelous spread of food. Rachel had created an incredible cake in the shape of a church, and Jeremy handed out flutes of champagne and gave a wonderful speech. But most special of all, as well as all talking together, we took the time to listen. At my mother’s suggestion, each of us present took it in turns, from the youngest child to the eldest friend, to ask my grandfather a question about his life and his work.

My grandparents held hands, and often Marcus would turn to Mary to complete the story or the answer they both knew so well. As ever, they were a perfect team …

Read more posts in the Every Voice series, which presents thought-provoking quotes showing how people all over the world give voice to URI.