The author during the religious sites’ tour in Herzegovina with URI members in front of Žitomislić Christian Orthodox Monastery in 2017. Photo: Private archive

Article written by Emina Frljak, Program Coordinator for Youth for Peace CC, Bosnia and Herzegovina:

Interfaith dialogue… A syntagma we see so often in media, a phenomenon researchers and scholars are writing and researching about more and more, a phenomenon that many governments and intergovernmental institutions insist is important to work on, a phenomenon that is an integral part of many local and international organizations.

Why is it so? Why do we insist and why do we need to work on interfaith efforts? And most importantly what does interfaith dialogue mean? How do we define it, where do we see it, what does interfaith look like and how does it “taste”?

I am not sure I will be able to answer all these questions in this short article, but I will try. This article is a mixture of personal reflections of a young woman involved in interfaith on local and global levels and a theoretical insight, where I will be relying on some works about interfaith dialogue. This is not an attempt to write an overall analysis of the state of interfaith dialogue today, but rather to offer a few reflections from my experience and research.

So why do we speak about interfaith at all? Do we really need it so much or is it “fancy” to speak or write about it? What has led us to this situation in which we need to work on interfaith efforts?

In her paper Marianne Moyaert (2013) states 4 factors that lead to more talks and more actions towards interfaith dialogue. Moyaert writes that “the first trigger for this altered attitude to religious plurality was the painful and dramatic history of the religious wars that ravaged Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, which showed how destructive interreligious disagreements could be”. (Moyaert, 2013: 196). As the second reason she mentions ecumenical dialogue that originated in 19th century with the attempt to break through the divisions between Christian denominations. This dialogue showed that it is possible to maintain positive relations with people who think and believe differently.

Third important factor according to Moyaert is the history of colonization and decolonization. European colonialism was fed with the ideology that local traditions were inferior, and they were portrayed as that. Because of this approach local traditions were seen primarily as “targets for outreach and conversion” (Moyaert, 2013). Finally, the fourth factor is the Shoah or Holocaust that cost the lives of 6 million of Jews.

It really made me think, did we really need to be that cruel towards each other to actually start thinking of trying to understand each other, and break the cycle of violence that some people and structures imposed and provoked for the sake of their quest to power. A huge part of humanity (including people of faith) accepted to be a part of the above-mentioned oppressions, persecutions, and killings. And even today, when interfaith efforts are multiplied all over the world, we are faced with wars and violence globally and it makes me think did we learn anything from our past or what we should do differently to not repeat the past?

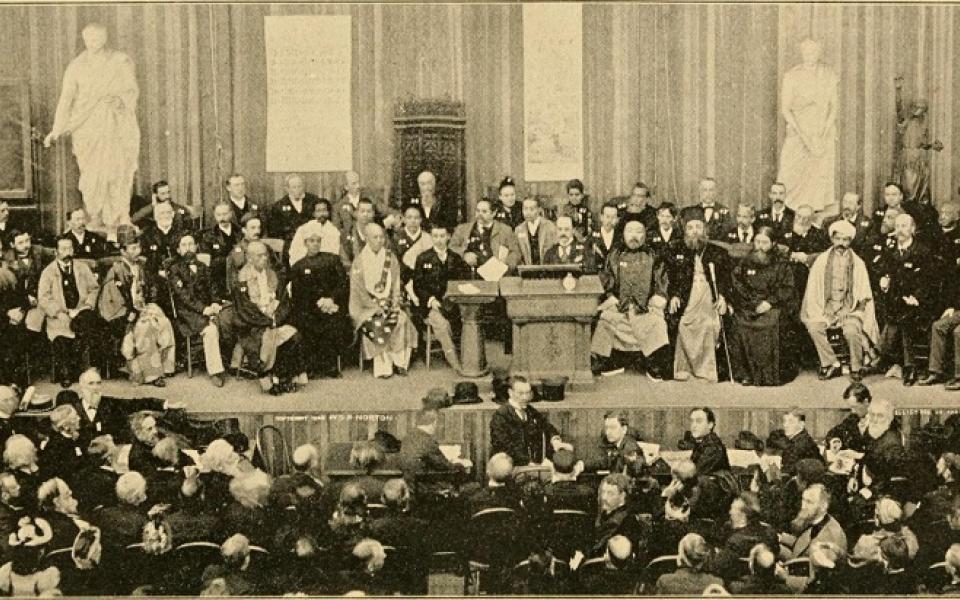

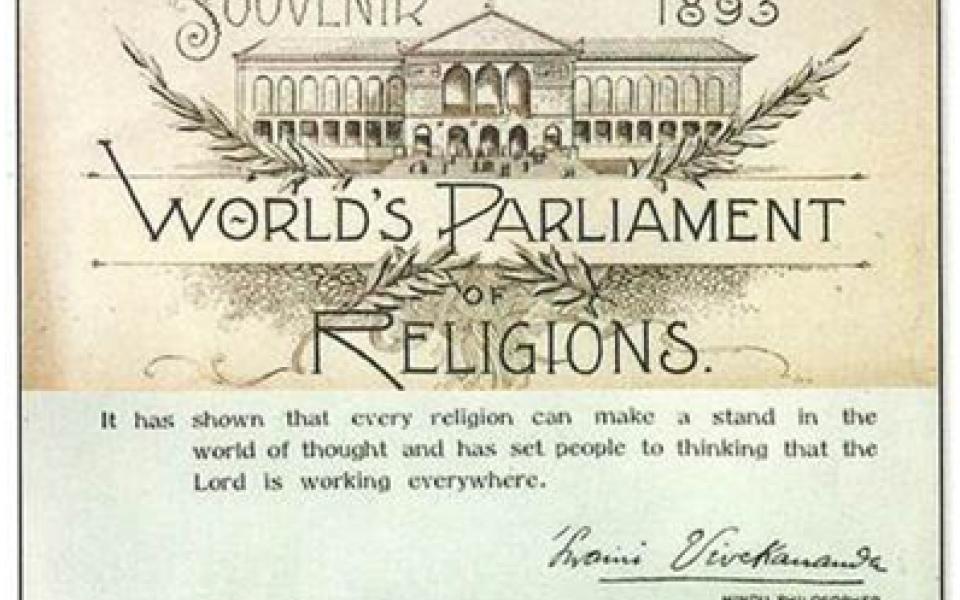

But how did it all start? When did we first start to take focused and systematic efforts to engage in interfaith dialogue? The 1893 event in Chicago World’s Parliament of Religions marked the first organized effort to gather representatives of different religions in one place and to talk about how we can live together. The event gathered 400 representatives of ten religions of the world: Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Taoism, Confucianism, Shintoism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam and more than 4000 people were present during the opening event. This event certainly is one of the milestones in interfaith dialogue, and the reader can find more about it on the page of the Pluralism Project by Harvard University and Katherine Marshall’s article The Parliament of the World’s Religions: 1893 and 1993.

World Parliament of Religions 1893. Photo from the The ARDA- Association of Religion Data Archives

A souvenir from the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions. Photo: Chicago Vedanta

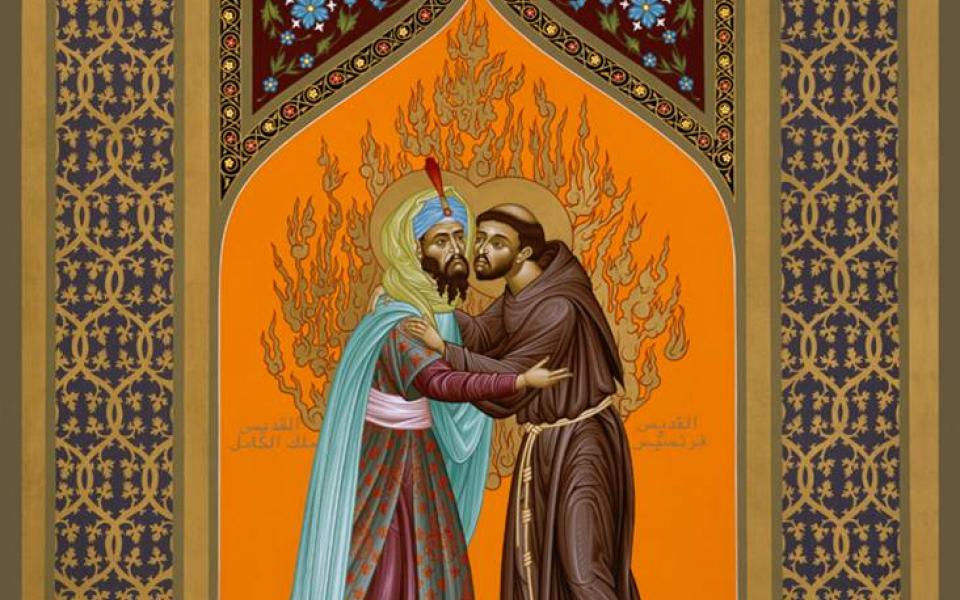

But before all these events, before the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions event, I have the need to go back much deeper in the past. I need to take us to the year 1219 where St. Francis of Assisi met with the Sultan of Egypt al-Malik al-Kamil. Their meeting happened during the Fifth Crusade, during quite a dark period of human history when people were fighting against each other in the name of God (I will not go into politics here, nor I will discuss possible ulterior motives of those who held the power back then). In all that death, in all that hatred and ignorance, a ray of hope came from these two men.

Of course, it is impossible to claim that this was the first major attempt of people to conduct interfaith dialogue, but certainly it is among the best-known ones. Probably in history many events like this happened, and many people were attempting to understand each other, rather than kill each other. But the history we learn about is full of wars, famous military leaders and generals, important battles, and violence. It seems that in the highly competitive and power-hungry world there was (is) no place for those who seek peace and are peacemakers even though “blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God” (Matthew 5:9). For those interested in the story of the St. Francis of Assisi and the Sultan al-Malik al-Kamil you might read more in the article by Dr. Paul Roth from Heythrop College, University of London or visit the page of the movie The Saint and the Sultan based upon their encounter.

The Saint and the Sultan. Photo: World Interfaith Harmony Week

Maybe, just maybe we speak about interfaith dialogue, and we seek interfaith actions, because our world today is highly polarized, because we are facing ecological catastrophe more than before, because we witness despicable violence committed against religious groups, but also committed in the name of religion. And interfaith dialogue is just one of the ways to address these pressing issues, but it is not enough. There is so much work to do and as a humanity we must work together and be able to face the reality, acknowledge it and then start changing it for the better.

But I don’t want to keep us in the past and certainly don’t want to create a grim and dark tone of the article, but I do find it important that we see the past and the present with our eyes and minds wide open and learn from it. To continue this reflection, I would like to briefly pay our attention to the types of interfaith dialogue and where interfaith does exist. Different authors and researchers propose different classifications, but here I will list the 5 types that Moayert mentions in her work. Those are:

- The dialogue of life – people of different religious traditions simply interact with each other in the context of their daily lives; this type of dialogue does not involve deliberate or intentional addressing of difficult theological questions; this can be an informal encounter between neighbours over a cup of tea or coffee, between co-workers in the workplace, parents in school etc.

- The practical dialogue of action – people of different religious traditions can work together on addressing pressing social, humanitarian, economic and political issues. This kind of dialogue rests on the fact that there are external challenges which all people are confronted with regardless of their religious tradition. Migrations, hate speech, injustice, ecological crisis, violence just to name a few.

- Theological dialogue – this dialogue is discursive and focuses on a specific theological topic such as Trinity, monotheism, the role of holy scriptures etc. So, the emphasis is on what is believed and doctrinal issues. The aim is to penetrate the precise meaning of certain ideas and concepts and create understanding.

- Spiritual dialogue/dialogue of experience – this type enables people to learn from one another through prayer and meditation. The starting point in this dialogue is the spiritual experience, which is the ultimate end of a deep religious quest.

- Diplomatic dialogue – in this type of dialogue, religious leaders are the central figures. These encounters are formal in their nature. This kind of dialogue has symbolic importance: it implies the willingness of religious leaders and institutions to leave the centuries-old hostilities behind.

Should the readers wish to know more about these types, I encourage them to read the full article and do research of the existing bibliography.

I find the diplomatic dialogue led by religious leaders as extremely necessary, though not the most important. Religious leaders are leaders for a reason, they are there to lead and guide their communities, they are there to pave the path and help people understand the importance of interfaith dialogue, genuine interfaith dialogue. With their example they need to show that cooperation matters, that loving our neighbours matters, that socializing and dialoguing with others won’t make us lesser Muslims, Christians, Jews, Hindus, Baha’is etc. But on the other hand, they lead by example, they do not impose or force anything on people and they are there to listen to the pulse of their communities. This is where the the dialogue of life and dialogue of practical action comes in. Dialogues that happen among people, among communities. In my humble opinion these types are of even greater importance. One must ask why? And here is my answer:

Religions do not exist in vacuum, they exist in one society side by side with social and economic processes, cultures, politics, customs, and traditions. And the most important thing is that they exist among people, among those who live those religions, who practice, among those who cherish and live values and beliefs and those who shape their lives according to religious scriptures, practices, and traditions. And that is why interfaith dialogue on these levels is so important.

The author with colleagues from Youth for Peace speaking about importance of interfaith dialogue in the post conflict context during CTEWC conference in Sarajevo, 2018. Photo: CTWEC

So what does this mean in practice? How can we practice interfaith dialogue?

An act of interfaith dialogue is when you share your iftar with your non-Muslim neighbour, when you visit your Christian neighbour for Easter and get eggs as a present, when you pay a visit to local gurdwara to learn something and meet your Sikh neighbours. Interfaith dialogue is when we can gather (offline or online) and pray side by side for the healing of our Mother Earth or to ask for Divine relief from COVID 19. When we are able to direct our prayers together, side by side, each in our faith tradition, with no need to be syncretic, to pray in our own way, but yet with similar messages to the Divine.

An act of interfaith is taking joint actions to protect people on the move and provide shelter, food, and support to them. Addressing gender-based violence from the perspective of our religious traditions through multifaith efforts is an act of us working together and facing challenges. Providing humanitarian support to those who were the most affected by COVID 19 together and providing the support to the people regardless of their religious or non-religious affiliation. Coming together, reading our scriptures with specific focus on certain topics employing the strategy of scriptural reasoning is certainly an act of interfaith dialogue.

But in my experience, we often tend to forget one important dimension of interfaith dialogue and that is the rights-based dimension. The dimension that sheds the light on the rights of those who are often minorities in our communities. All the mentioned acts are not enough to sustain interfaith dialogue, if we don’t acknowledge that our neighbours have the same rights as we have. If we don’t acknowledge that each and every one of us have the right to have religious sites, have the right to congregate and have the right to express our own beliefs in public without fear of being discriminated against or persecuted. And just as acknowledging this, it is important to actively work that our fellow neighbours really fulfil their rights.

With this approach, comes the humility and idea that in dialogue we need to enter as equal partners, without patronizing or imposing one religion over the other and we need to make sure that all we do in dialogue is genuine and not for the sake of proselytizing.

The author during the Muslim-Jewish Conference in Jewish Museum (former Sephardic synagogue) in Sarajevo in 2017. Photo: Private archive

For the end of this reflection, I would like us to remember that religions do not dialogue, but people who belong to religious communities do.

In the interfaith dialogue it is not Islam dialoguing with Christianity, Judaism speaking to Buddhism etc. it is people of different and diverse religious backgrounds speaking to each other. And when entering into dialogue, it is important to come with an open mind and heart. It is important to be able to listen, to understand and to accept that our partners in dialogue hold different beliefs and values sometimes even contrasting our own. Yes, it is about finding and celebrating our similarities, but also about speaking and understanding our differences, our contrasting views.

It is about being genuine, about speaking out and even agreeing to disagree, because the purpose of interfaith dialogue is NOT that we all become THE SAME, the purpose is to have the ABILITY TO ACCEPT DIFFERENCES and to accept that other people don’t hold the same beliefs and opinions as we do and BEING IN PEACE WITH THAT.

So, if we want interfaith dialogue to succeed, we must ask ourselves are we able to sit with and accept that my partner in dialogue doesn’t believe in the same sacred principles as me, that my partner in dialogue doesn’t hold the same values that I hold important. It is really a question: are we able to be genuine, are we able to come to dialogue without ulterior motives and are we really ready to understand that my religion might be the best for me, but not for my partner in dialogue.

One important question that emerged at the very beginning of interfaith dialogue efforts, but is still relevant today is: How can one find a balance between one's own faith commitment and openness to the otherness of the other? I think this is a question that each of us has to reflect on and reason with, and in the end answer for ourselves.

After entering the interfaith sphere, it took me quite a lot of time, and a lot of dialoguing with myself to answer this question. And still, I think about it and still I shape and re-shape this answer, but one thing I know is that without interfaith I wouldn’t be who I am today, I wouldn’t be able to understand my religion the way I understand it know, I wouldn’t be able to embrace my female Muslim identity the way I embrace it now and I wouldn’t be eager to speak about my religion so openly and feel belonging to the world, to the humanity and the planet as I feel now.

The author speaking about interreligious education during the RfP Multi-religious and Multi-stakeholder Partnership for Peace and Development in New York, 2019. Photo: Flickr Religions for Peace

Emina Frljak is a Program Coordinator within Youth for Peace, an organization based in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ms. Frljak also serves as International Youth Committee Member within Religions for Peace. She is also a Board Member of European Interfaith Youth Network of Religions for Peace.

Ms. Frljak holds a BA in Educational Sciences of University of Sarajevo, where she is completing her MA in the same field. She is also pursuing her second MA in Interreligious Studies and Peacebuilding, a joint program of three theological faculties in Bosnia and Herzegovina.