The real danger of a nuclear catastrophe is not from a planned attack from Russia, which is what our defense strategy implicitly assumes. Our real danger is from an accident, such as responding to a false alarm, or a political miscalculation.

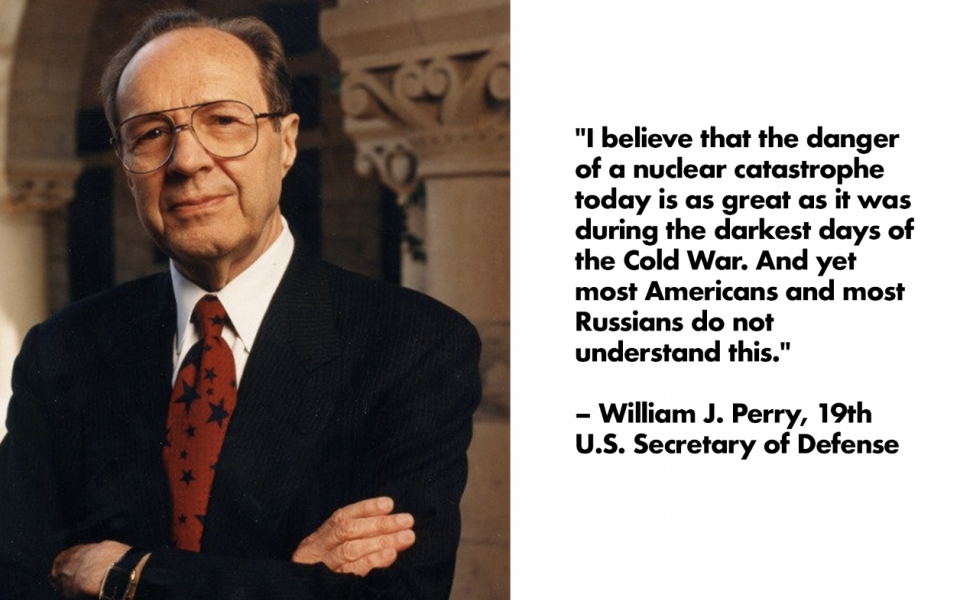

I had the privilege to invite William J. Perry, former Secretary of Defense and Voices Founding Member for the following Deep Dive. I asked Secretary Perry if he would speak to what he sees are the greatest threats we face today and what can be done about them. Here is his in-depth response.

Thank you, Secretary Perry, for sharing your expertise and insights with us!

– Julie Schelling, Voices Outreach & Communications Coordinator

I believe that the danger of a nuclear catastrophe today is as great as it was during the darkest days of the Cold War. And yet most Americans and most Russians do not understand this. Most people think that the danger of a nuclear war ended with the ending of the Cold War. As a result, the nuclear policies of Russia and the U.S. do not reflect the perilous position we are in. And the danger increases as other countries seek to enter the nuclear club; North Korea already has a nuclear arsenal and Iran is threatening to get one. But is it likely that any nuclear power will actually use the bomb? Since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, no country has ever done so.

Deterrence seems to work. So why do I think the danger is so great? And what can we do to lower this danger?

My paper will address those two questions. But first, some relevant history. During the Cold War, the U.S. believed that the Soviet Union was building up its nuclear forces so that it would be able to launch a surprise, disarming nuclear attack on the U.S. At the same time, the Russians believed that we were building up our nuclear forces for a surprise attack on them. Those dynamics drove an arms race that in time resulted in each country having a nuclear arsenal of over 30,000 weapons, far in excess of greater than what was needed for deterrence. This arms race entailed huge costs and great dangers, but both nations believed that it was necessary for their survival.

The Cold War ended in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and in the decade of the 1990s each side began a nuclear dismantlement program that took its arsenal down from 30,000 weapons to about 5,000, along with an end to hostile relations. During this period, I was the Secretary of Defense, and I worked closely with my Russian counterpart, almost as if we were allies. We oversaw major reductions in each country’s nuclear arsenals. Together we dismantled 8,000 nuclear weapons during the three years that I was Secretary of Defense.

I thought that this dismantlement program would continue because we still had many more weapons than were needed for deterrence, and because we had developed such good relations with Russia. But even during this period of goodwill and cooperation the United States never gave up its policies and implicit belief that the primary threat to the U.S. was a surprise nuclear attack from Russia, and with the return of hostilities early in the next century that belief became explicit. Indeed, during this past decade that hostility has become so intense that it became what can fairly be called Cold War 2.

Now, just as in the Cold War, we keep our nuclear weapons on high readiness so they can be launched in a few minutes if we get an alert that a Russian attack is underway. This practice is called LOW: Launch on Warning. And the Russians do the same. That is incredibly dangerous. In fact, the greatest nuclear danger today is that the quick launch posture of the United States and Russia could lead to an accidental nuclear war.

How could this happen?

Since The United States believes that our greatest threat is a surprise disarming attack from Russia, we have postured our nuclear forces today, just as in the Cold War, so that they can be launched within a few minutes of a launch order from the president. And we have developed a surveillance system that can detect a Russian launch with a few minutes after its liftoff, and a communication system that can transmit such detections to our command center where it is analyzed and evaluated.

If the command center concludes it is a valid launch it communicates this to the president, he will have perhaps five or ten minutes to decide whether to launch our ICBMs before they are destroyed in their silos. This is a truly amazing technical system, and it works very well nearly all the time. In fact, it has only led to false alarms a handful of times. The problem, however, is that it only takes one false alarm to start a nuclear war by accident.

If the president makes a launch decision our missiles will be on the way in a few minutes, and he cannot call them back or destroy them in flight if he later determines that it was a false alarm. That is, he will have started a nuclear war by accident. In the false alarms we have experienced to date, we have always caught the false alarm before the president made a launch decision, but on one occasion during the Cold War, it very nearly led to a disaster. At the time I was the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering. On the night of the false alarm I was awoken by a phone call in the middle of the night from the watch officer of the North American Air Defense Command who told me that their computers were showing 200 missiles on the way from the Soviet Union to the United States, Happily, he quickly added that he had determined that it was a false alarm and he was calling me to see if I could help him figure out what had gone wrong with their computers. But before he had determined it was a false alarm, he had called the White House to alert the president. The president’s National Security Advisor took the call and believed that an attack was underway. He was about to waken the president to tell him that he had about five minutes to decide whether to launch our ground-based missiles before they were destroyed in their silos. But before the National Security Advisor woke the president, he got a follow up call from the watch officer telling him that it was, in fact, a false alarm.

The watch officer then called me for assistance in determining what have gone wrong with his computers. That night I was not able to determine what had malfunctioned. It took several days to locate a faulty chip in one of the computers. It was a simple equipment malfunction, easily fixed but potentially catastrophic. This starkly illustrates the danger of starting a nuclear war accidently because of a technical error or human error. To date such errors have always been caught before it was too late—but humans and machines will continue to err.

And there is the additional danger of starting a nuclear war by making a political miscalculation. The most striking historical example of that is the Cuban missile crisis. In that crisis both Kennedy and Khrushchev were doing everything they could to avoid a nuclear war, but both had military advisors advising them to take military action, and both were acting on information that was often wrong.

After the crisis, Kennedy said that he thought the chances of the crisis erupting into a nuclear war were about 1 in 3. But when he said that he was not aware that the Soviets, besides having the medium-range missiles that were not yet operational, also had in Cuba short-range missiles that were operational and that were mated with nuclear warheads. If Kennedy had ordered military action against Cuba, as the Joint Chiefs of Staff were recommending, our troops would have been decimated on the beachhead by tactical nuclear weapons, and a general nuclear war would surely have followed.

Sadly, the hostile relations between the United States and Russia today create the breeding grounds for another political miscalculation. It is not clear where and how that could occur: in the Baltics, in Ukraine, or on the borders of Russia where we regularly conduct patrols with reconnaissance aircraft and ships.

So, we still face the danger of a nuclear conflict. But the danger is not a planned attack from Russia. The Russians are not suicidal; they are not stupid; deterrence works.

The real danger of a nuclear catastrophe is not from a planned attack from Russia, which is what our defense strategy implicitly assumes. Our real danger is from an accident, such as responding to a false alarm, or a political miscalculation. Neither is likely, but both have happened; and when they did, we avoided a nuclear catastrophe by intelligent people making intelligent decisions; but also, by good luck. The survival of our civilization should not depend on our continuing to have good luck.

Hiroshima was destroyed by one nuclear bomb with a destructive power of about 15 kilotons. Most of the thermonuclear bombs in the military forces of the United States and Russia have a destructive power ten times greater, and many of them have a destructive power a hundred times greater. Each of our countries has about 4,000 thermonuclear weapons in its nuclear arsenal, of which 1,550 are deployable. The tragedy that occurred 75 years ago led to the destruction of two cities and about 200,000 deaths. A nuclear war today could result in hundreds of cities being destroyed and many tens of millions dead, even discounting the worldwide environmental disaster that could lead to the end of our civilization.

Thus, our nuclear weapons pose an existential threat to mankind. And the only lasting solution to this deadly problem is to abolish nuclear weapons. Many people have pursued this objective but have encountered huge practical and political problems. The first really dramatic move in that direction came in 1986 when Reagan and Gorbachev met in Reykjavik, where they discussed both countries giving up all of their nuclear weapons. They came close to an agreement to abolish nuclear weapons but foundered on a disagreement about what to do with ballistic missile defenses.

But there were at least three positive outcomes of that meeting: The landmark INF treaty (now sadly abandoned by the U.S. and Russia); the memorable phrase: “A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” and, most importantly, making the idea of abolishing nuclear weapons thinkable.

Two decades after Reykjavik, George Shultz, who had been with Reagan at Reykjavik in his capacity as Secretary of State, was still thinking about it and decided to revisit that meeting. What resulted from that reconsideration was a series of editorials in the Wall Street Journal. George asked me, as well as Henry Kissinger and Sam Nunn, to join him in co-authoring the editorials, which described the dangers of nuclear weapons and called for their abolition.

The response to them was surprisingly strong, leading to many invitations to speak about why we had come to believe in nuclear abolition, after long careers in supporting robust nuclear forces for the United States. For the next few years, we travelled worldwide as apostles of nuclear abolition. We were invited to meet the heads of state of Russia, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. We were particularly encouraged by President Obama’s reaction. Only a month after he took office in 2009, he travelled to Prague to make his memorable speech on nuclear dangers:

“I speak clearly and with conviction the commitment of the United States to seek the peace of the world without nuclear weapons.”

I was thrilled when I heard his speech and was convinced that we were going to be successful. It seemed that the “Impossible Dream” of abolition might actually happen. Subsequently President Obama succeeded in reaching an agreement with Russia for an arms control treaty, New START, for the reduction of the nuclear weapons of Russia and the United States. Without doubt, the day of the signing of New START (April 8, 2010) was the high point of our crusade to abolish nuclear weapons.

But from that day on it went precipitously downhill.

The treaty became a victim of partisan politics. President Obama was not able to get ratification during the regular term of the Senate that session. After the Senate term closed in October, he conducted intensive, closed-door negotiations with the opponents of the treaty. The result of those discussions was his agreement to support the defense spending bill favored by the treaty opponents (including a large program of nuclear modernization) and their agreement to let the treaty be ratified. Following that agreement, the treaty was ratified in the lame duck session in December, but at a price that I believe was too high. Another implicit consequence of the fight to get the treaty ratified was President Obama’s apparent conclusion that the price he paid for the ratification and the heavy drain on his time it had entailed precluded his continuing forward with his goal of major reductions in nuclear weapons.

We are now programmed to rebuild our nuclear arsenal over the next few decades with entirely new weapons to replace all our present ones, at a cost of over a trillion dollars. Russia, of course, has an equivalent program, which President Putin described in a State of the Federation speech as one of his major achievements.

It seemed that my “impossible dream” really was impossible, at least at this time, but there are many actions we can take, each of which would make the world safer. These actions will not be easy to take, since they would be overturning policies that have been in place for decades, but I believe that, with a determined effort, we could achieve many of them.

The first action would be revoke presidential sole authority. The American president has the sole authority to order the use of nuclear weapons. He may consult with others, but he is not required to. He has with him at all times the communication equipment (famously called the Football) and the codes to order a launch that would be then carried out a few minutes later. This is incredibly dangerous because of the possibility of his reacting to a false alarm. It is also dangerous because of the possibility that the president could be impaired for some reason: heavy drinking, heavy medications, or onset of Alzheimer Disease, (all of which have happened).

The Biden administration should revoke sole authority and require the involvement of some members of Congress in any decision to use nuclear weapons unless nuclear weapons have already been used against us.

President Biden also should state that the sole purpose of our nuclear arsenal is to deter a nuclear attack and we will never use them first. These actions would be politically difficult for the president, but they are not “Mission Impossible”. And they would make us all safer.

Stanford’s Professor William James Perry has distinguished himself as a mathematician, engineer, and pioneering entrepreneur. He’s best known, however, as a major player in the United States Department of Defense in the 1980's and 1990's, renowned for his expertise in foreign policy, national security, and arms control. Under President Bill Clinton he served as United States Secretary of Defense from 1994-97. In 2013 Professor Perry established The William J. Perry Project “to educate the public on the dangers of nuclear weapons in the 21st century.” Today the Project, housed at Stanford University, is a virtual library of resources that can bring the anti-nuke neophyte up to speed on the major issues associated with nuclear weapons and human survival.